Dear Make-Up Artists of 2012,

Take a bow, ladies and gentlemen. You've earned your moment in the spotlight. True, your success (like most professions within the film industry) is usually measured by how little you stand out in the storytelling process. But every few decades, make-up artists hit a new milestone that forces the general public to take notice. I have every confidence that 2012 belongs among those banner years. We've seen incredible achievements (Looper), awkward failures (Prometheus) and raging controversies (Cloud Atlas). But most important, we've seen a compelling argument for why, at a time when photo-realistic digital technologies threaten to make your job obsolete, prosthetics still have a vital place in cinema.

Part 1: Making-up History

Even before cinema, make-up has served two important functions: to be corrective (covering flaws and emphasizing attractive features) and creative (building imaginative new characters on actors). Silent film actors would often apply their own pancake make-up when high contrast orthochromatic film was used. But as new panchromatic stocks allowed cinematographers to differentiate the entire light spectrum as subtle shades of gray on black and white film, the task quickly fell on specialists like yourselves to evolve the trade for the medium.

<<<<<<< HEAD <<<<<<< HEAD

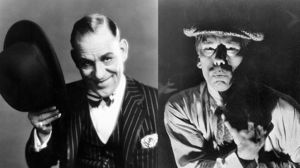

Lon Chaney Sr. - Hollywood's first famous make-up artistLon Chaney Sr. was the first to turn his own face into a shocking work of art for filmgoers. His renditions of Quasimodo for The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and the unmasked man in The Phantom of the Opera (1931) preserved the character's humanity behind the plaster with legendary results. Jack Pierce followed suit with Frankenstein (1931), and became an inventive pioneer in the trade, relying on scientific and surgical techniques to mold rubber latex into the everlasting images from The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dracula (1931), and a treasure chest of monsters for Universal Studios. Chaney and Pierce's fierce rivalry would push them through many innovations and come to define the medium for a generation.

But household names were hard to come by when most make-up artists didn't even receive a screen credit for their work. Maurice Seiderman, for example, was simply an unqualified but ambitious hair sweeper for RKO when he insisted he could turn a 25-year-old Orson Wells into a decrepit 70-year-old using elastics to trigger muscle reactions. He won the job and still wins acclaim for his work 70 years later, even if you won't see his name listed on the film itself. Only when unmistakable examples of excellence presented themselves, as they did in the 1960s, did the Academy Awards create special honorary Oscars for William Tuttle's transformations for The 7 Faces of Dr. Lao _(1964) and John Chambers' advances for _Planet of the Apes (1968). But it would take the unfathomable snub of ignoring Christopher Tucker's spellbinding work on The Elephant Man (1980), created from real-life casts of John Merrick's body, to push your profession into its own regular category for the Academy Awards. Fittingly, the first recipient of the annual prize would go to Rick Baker the very next year for his incredible designs on An American Werewolf in London (1981). Baker has gone on to be a perennial contender for the prize, winning seven Oscars and getting his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just this year.

Rick Baker (left) with American Werewolf in London director John Landis

Lon Chaney Sr. was the first to turn his own face into a shocking work of art for filmgoers. His renditions of Quasimodo for The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and the unmasked man in The Phantom of the Opera (1931) preserved the character's humanity behind the plaster with legendary results. Jack Pierce followed suit with Frankenstein (1931), and became an inventive pioneer in the trade, relying on scientific and surgical techniques to mold rubber latex into the everlasting images from The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dracula (1931), and a treasure chest of monsters for Universal Studios. Chaney and Pierce's fierce rivalry would push them through many innovations and come to define the medium for a generation.

But household names were hard to come by when most make-up artists didn't even receive a screen credit for their work. Maurice Seiderman, for example, was simply an unqualified but ambitious hair sweeper for RKO when he insisted he could turn a 25-year-old Orson Wells into a decrepit 70-year-old using elastics to trigger muscle reactions. He won the job and still wins acclaim for his work 70 years later, even if you won't see his name listed on the film itself. Only when unmistakable examples of excellence presented themselves, as they did in the 1960s, did the Academy Awards create special honorary Oscars for William Tuttle's transformations for The 7 Faces of Dr. Lao _(1964) and John Chambers' advances for _Planet of the Apes (1968). But it would take the unfathomable snub of ignoring Christopher Tucker's spellbinding work on The Elephant Man (1980), created from real-life casts of John Merrick's body, to push your profession into its own regular category for the Academy Awards. Fittingly, the first recipient of the annual prize would go to Rick Baker the very next year for his incredible designs on An American Werewolf in London (1981). Baker has gone on to be a perennial contender for the prize, winning seven Oscars and getting his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just this year.

FETCH_HEAD

Lon Chaney Sr. was the first to turn his own face into a shocking work of art for filmgoers. His renditions of Quasimodo for The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and the unmasked man in The Phantom of the Opera (1931) preserved the character's humanity behind the plaster with legendary results. Jack Pierce followed suit with Frankenstein (1931), and became an inventive pioneer in the trade, relying on scientific and surgical techniques to mold rubber latex into the everlasting images from The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dracula (1931), and a treasure chest of monsters for Universal Studios. Chaney and Pierce's fierce rivalry would push them through many innovations and come to define the medium for a generation.

But household names were hard to come by when most make-up artists didn't even receive a screen credit for their work. Maurice Seiderman, for example, was simply an unqualified but ambitious hair sweeper for RKO when he insisted he could turn a 25-year-old Orson Wells into a decrepit 70-year-old using elastics to trigger muscle reactions. He won the job and still wins acclaim for his work 70 years later, even if you won't see his name listed on the film itself. Only when unmistakable examples of excellence presented themselves, as they did in the 1960s, did the Academy Awards create special honorary Oscars for William Tuttle's transformations for The 7 Faces of Dr. Lao _(1964) and John Chambers' advances for _Planet of the Apes (1968). But it would take the unfathomable snub of ignoring Christopher Tucker's spellbinding work on The Elephant Man (1980), created from real-life casts of John Merrick's body, to push your profession into its own regular category for the Academy Awards. Fittingly, the first recipient of the annual prize would go to Rick Baker the very next year for his incredible designs on An American Werewolf in London (1981). Baker has gone on to be a perennial contender for the prize, winning seven Oscars and getting his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just this year.

FETCH_HEAD

And yet, the 1980s are often heralded as the last great gasp of make-up effects before the incredible advances of computer generated images (CGI). Just as the profession had to reinvent itself with the advent of new film stocks and colour pictures, high-definition televisions and motion capture technology have created the need for more innovations, which in 2012 have been answered in subtle and stunning ways.

Sincerely,

Christopher