Practical make-up effects are one of the elements I love most in filmmaking. As digitized gimmickry overwhelms the look of more and more films, the presence of something physical - even something as simple as a fake nose - can really define how an actor interacts with (or is reacted to by) others. Over the years, as make-up techniques have advanced, filmmakers have found themselves with more tools to work with, and actors, unburdened, are able to perform with more subtlety.

But one particular specialization seems to have remained for the large part un-evolved: old age make-up.

I'm not blaming you for this, Stephen. It's just something that's always bothered me. Seeing actors struggling to emote while encased in fake wrinkles, jowls, and wigs is, at best, distracting--and, at worst, depressing. We have come a long way from Dustin Hoffman's mummified face in Little Big Man, but we haven't come far enough; old-age prosthetics sacrifice life and subtlety for surface detail. And this is exactly the problem with Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.

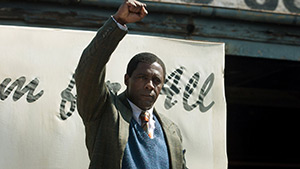

Director Justin Chadwick's adaptation of Nelson Mandela's autobiography takes on so much of Mandela's life that it is never able to break the surface. It's a collection of scenes that provides a nice overview, but far too little insight. It's not that the material wasn't there. Both Idris Elba, as Nelson Mandela, and Naomi Harris, as his second wife Winnie, give great performances--almost worth the price of admission alone. Particularly in the early scenes, they shine: Mandela begins as a lawyer more interested in hitting the bars and chasing girls than becoming a voice in the anti-apartheid movement, and, eventually, a leader of the early African National Congress.

Elba is one of the few actors who could convey both the anger and charisma that drew people to Mandela. It's a side of Mandela not many may be familiar with, and, better developed, would have made his transformation into the recently deified figure that much more striking.

Instead, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom expands its scope and tries to be two things at once: a summary of Mandala's life and the story of his disintegrating relationship with Winnie. Once Mandela begins his decades-long imprisonment, Chadwick divides the film between Nelson and Winnie, using Winnie's story as a means to illustrate the utter chaos and horror South Africa went through in the 70s and 80s. But the more content the film tries to include, the more it sags under its own weight. No moment is given proper time to develop and therefore has little impact. And, as the years pass--and the latex piles on--Mandela is reduced to speaking in platitudes, and our attention is lost in an awkward attempt to find the visual middle ground between Elba's and Mandela's faces. The movie stiffens along with Elba's face.

The effect is to render Mandela a passive figure in his own life. Chadwick isn't able to find a way to dramatize Mandela's personal transformation. That is certainly the harder story to tell cinematically, but it is also the central story to Mandela's life. And as Chadwick focuses on events occurring outside the prison walls, he keeps returning to Mandela in scenes that increasingly feel like prison visits, each lasting only long enough for Mandela to espouse some vague piece of wisdom before moving on.

We know there's a lot more to Mandela than that. It's a tribute to Elba's performance that even under all that weight, his fire and intelligence manage to shine through at all. But all too often he is left to suffocate beneath the mask you crafted. In ignoring the illuminating details of Mandela's journey, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom stumbles long before it arrives at its destination.

Sincerely,

Casey